By Jonathan D. Glater

To be a partner at a major law firm is a virtual lock on wealth, prestige and influence. To achieve that lofty goal, young lawyers willingly pore over deadly dull documents, draft amply footnoted briefs of inordinate length, shmooze with clients no matter how boorish and work around the clock. But just what, exactly, it takes to make partner is elusive. A provocative new study of the reasons big law firms have so few minority partners claims there is a simple answer: grades.

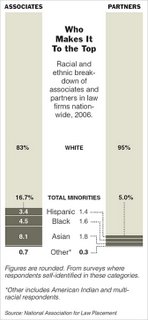

Richard H. Sander, a law professor at the University of California, Los Angeles, who prepared the study, wrote that there is a “credentials gap” between white and black law school graduates that may explain why black lawyers do not make partner. He also found smaller gaps affecting Asian-American and Hispanic law students. The study, which comes as attacks on affirmative action have gained strength in recent months, focuses on the low numbers of minority partners at law firms. Of the 60,394 partners at 1,523 law firms that provide data to the National Association of Law Placement, nearly 95 percent are white.

Partners at elite law firms acknowledge the numbers are low. But they said grades received years earlier in law school had little to do with promotion. “You don’t want to know about my grades,” said Reid H. Weingarten, a well-known litigator at Steptoe & Johnson in Washington, who is white. Partners at top-tier firms said grades mattered in hiring first-year associates, who may receive $135,000 a year (not including the bonus). But when deciding whom to make a partner, they said grades were not a factor. In fact, promotion decisions can be very subjective, dependent on perception as well as output. Research shows that informal networks within firms may exclude young minority lawyers.

“We look for people who are good working in teams, people who show the potential to be a builder of a practice, through enhancing the reputation of the firm, enhancing and developing loyal client relationships,” said Keith C. Wetmore, chairman of Morrison & Foerster in New York. Grades might show willingness to work long hours, but not judgment or people skills, which are harder to evaluate objectively, many partners said. Eric A. S. Richards, a partner and member of the partner admission committee at O’Melveny & Myers in Los Angeles, said that partners tried to predict whether rising associates could bring in business. “We look for the promise,” he said.

When Mr. Sander described a causal connection between low grades and success at law firms, he cited a separate survey of law graduates of the University of Michigan. He said the study found that those who were still at firms 15 years after graduation — who were more likely to have made partner — had higher grades. That survey included about 10,000 lawyers, the vast majority of them white, the professor said.

But African-American, Latino and Asian lawyers are not the only ones who are underrepresented as partners. Women, who for years have been close to 50 percent of the law school students and make up 44 percent of the associate population, are just under 18 percent of all partners even though their law school grades are, overall, slightly higher than those of white men. Mr. Sander said that women in recent years had been making partner at higher rates, and noted that women may more often leave firms to create time for family or for other reasons.

Minority lawyers may also leave voluntarily, said David B. Wilkins, director of the program on the legal profession at Harvard, adding that they constantly receive offers from clients seeking to poach them. Mr. Sander has also written a study of law school admissions, arguing that because of racial preferences, law schools admit students who are less prepared and perform poorly — earning the lower grades. The system, as he sees it, is unfair to minority students because it sets them up for failure. “In both situations, we have preferences arguably undermining their intended effects,” he said, adding that the solution was to reduce preferences and improve training and support for minority lawyers.

But several senior lawyers said that because law firms are not such strictly objective meritocracies, hiring only minority lawyers with higher grades would not necessarily mean more minority partners. Many intangible factors, including luck, play a role. In a lean year, a firm will be reluctant to increase the number of partners splitting profits. A firm might promote a mediocre partner who speaks a specific language or has some other skill.

Then there are the all-important relationships formed between young lawyers and senior partners, said Theodore V. Wells Jr., a partner at Paul Weiss Rifkind Wharton & Garrison, who is black. “What happens very often is some associates are embraced more than others and it’s easier to fit in,” Mr. Wells said. “If you’re a minority person in a majority firm there are inherent difficulties.”

Diara M. Holmes, a Washington lawyer who last week made partner at Caplin & Drysdale, in Washington, attributed much of her success to mentors. “A mentor advocates on your behalf, obviously in the final decision but along the way as well,” said Ms. Holmes, who is the firm’s first African-American partner. “A mentor is also a person who can ensure that when you make mistakes, which is inevitable in an associate’s career, they do not cause you to fall off the track. I can’t imagine that my ‘A’ in property got me here.”