The Historical Development of Language And Cultural Diversity in the United States and California by Chinaka DomNwachukwu, Ph.D.

Dr. DonNwachukwu attempts to explain the predominancy of English in the United States within a historical context and analysis. "In order to appreciate the historicity of America's multilingualism we must first explore historical time periods that mark the American history, and appreciate the extent to which diverse languages have characterized the American Peoples from time immemorial." Dr. DonNwachukwu continues to summarize the evolution of English as the predominate language in America during its historic milestones. He explains that language in New England colonial America was controlled by English speaking Western European immigrants. Any German or Irish immigrants quickly "assimilated into the Anglo-Saxon socio-political, economic and language structure that dominated that era." Even post-colonial America continued to stress cultural homogeneity. "Given the fact that schooling was a community-based affair, dual language instruction was not a problem in post-colonial America. Most communities educated their young ones in their own languages and taught them the dominant language if English at the same time." Considering that all government functions and commercial/legal transaction were in English, all native languages would have been considered secondary to proper fluency in English. The challenge to English as the predominate language would have appeared during the great wave of immigration between 1900 and 1920s. Any possibility that Irish or German could predominate English was tempered by Anglo-Saxon protestant discrimination of Irish Catholic immigrants and anti-German WWI propaganda. "During this period, most American schools were being persuaded to eradicate dual language instruction and conform to the Anglo-Saxon culture and language."

"The Civil Rights movement of the early 1960s (further) intensified the need to address the learning opportunities for non-English speaking minority children." The Supreme Court ruling, Lau v. Nichols (1974) established that students who do not speak English may not be receiving an equal education. The Equal Education Opportunity Act (EEOA) passed in 1974 stated "that schools with second language learners are required by law to provide them with meaningful education by taking appropriate measures to overcome barriers that impeded on equal education opportunities."

Upon exploring the historical development of language in America, Dr. DonNwachukwu discusses multicultural education in his essay entitled, "Historical, Legal and Intellectual Foundations of Cultural Diversity in the United States & California". Dr. DonNwachukwu pointedly addresses the issue, "When and why did it become necessary to require the educational system to cater to the needs of all students represented in the school systems, and how has that attempt progressed over the years?" Dr. DonNwachukwu explains that only after the gains of the Civil Rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s could significant barriers erected by racial and ethnic preducies and bias, could any development in multiculturalism be achieved. "The impact of the civil rights movement and the laws that followed it are more evident when you consider the fact that from 1800s to 1968 African Americans were practically invisible in the major newspapers of Los Angeles." ""Whereas the laws have made general provisions for the pursuit of equality and multicultural education, multiple scholars and academicians have produced research insights that are changing minds, attitudes, and behaviors, making the provisions of law more acceptable to people in such a pluralistic democracy as the United States of America."

Friday, October 16, 2015

Thursday, September 17, 2015

White Mischief - The passions of Carl Van Vechten

by Kelefa Sanneh

In the summer of 1925, Carl Van

Vechten, a New York hipster and literary gadabout, sent a letter to Gertrude

Stein, whose friendship he was cultivating. Stein had finally found a publisher

for "The Making of Americans," but Van Vechten was preoccupied with a

project of his own. He called it "my Negro novel," though he hadn't

started it yet. "I have passed practically my whole winter in company with

Negroes and have succeeded in getting into most of the important sets," he

wrote. "This will not be a novel about Negroes in the South or white

contacts or lynchings. It will be about NEGROES, as they live now in the new

city of Harlem (which is part of New York)." A few weeks later, Stein

replied, using a word that Van Vechten didn't. "I am looking forward

enormously to the nigger book," she wrote.

When Van Vechten first arrived in

New York, in 1906, there were few signs that he would ever attempt to appoint

himself bard of Harlem. He was a self-consciously sophisticated exile from the

Midwest, and he was quickly hired by the Times as a music and dance critic.

Celebrating provocateurs like Igor Stravinsky and Isadora Duncan, he trusted

that the chattiness of his prose would make up for the occasional severity of

the art he loved. (In an early collection of his criticism, he sought to

reassure unseasoned listeners: "Don't go to a concert and expect to hear

what you might have heard fifty years ago; don't expect anything and don't hate

yourself if you happen to like what you hear.") He also published a series

of mischievous novels that were notable mainly, one critic observed, for their

"annoying mannerisms," including a lack of quotation marks and a

fondness for "obsolete or unfamiliar words." This verdict appeared on

the front cover of one of those novels, which was a clue that the anonymous

critic was Van Vechten himself. The more time Van Vechten spent in New York,

though, the more interested he became in the sights and sounds of Harlem, where

raucous and inventive night clubs were thriving under Prohibition. His ‘Negro

novel’ was meant to be a celebration, but Van Vechten couldn't resist giving it

an incendiary title: "Nigger Heaven," after a slang

term for the segregated balcony of a theatre. His idea was that the term might

serve as a suitably ambivalent analogy for Harlem. In a soliloquy halfway

through the book, one character explains:

Nigger

Heaven! That's what Harlem is. We sit in our places in the gallery of this New

York theatre and watch the white world sitting clown below in the good seats in

the orchestra. Occasionally they turn their faces up towards us, their hard,

cruel faces, to laugh or sneer, but they never beckon.

Various people urged Van Vechten to

reconsider, including his father. "Whatever you may be compelled to say in

the book," he wrote, "your present title will not be understood &

I feel certain you should change it." Van Vechten felt equally certain

that he should not: he didn't mind drawing some extra attention to his novel,

and, besides, he had Negro friends who would defend him.

In the end, Van Vechten and his father were both right. A

number of Negro critics were annoyed by the title, and offended by the novel's

lurid depictions of cabaret life-even though its main protagonists were smart,

college educated young Negroes who talked incessantly about art and literature.

But many white critics were impressed, and the controversy helped make

"Nigger Heaven" a best-seller. The book's marketing campaign was

designed to exploit white readers' fascination with uptown night life. (An advertisement

in The New Yorker asked, 'Why go to Harlem cabarets when you can read 'Nigger

Heaven'?") And its success helped draw attention to a movement: the Negro

Renaissance, which came to be known, and celebrated, as the Harlem Renaissance,

a name that conjures up both novelists and night clubs. It is possible that

"Nigger Heaven" did more for the Harlem Renaissance than it did for

its author, whose reputation never quite recovered from the backlash he faced.

Decades later, Ralph Ellison remembered him as a bad influence, an unsavory

character who "introduced a note of decadence into Afro-American literary

matters which was not needed." And, in 1981, the historian David Levering

Lewis, the author of a classic study of the Harlem Renaissance, spoke for many

when he called "Nigger Heaven" a "colossal fraud," an

ostensibly uplifting book whose message was constantly upstaged by "the

throb of the tom-tom." He viewed Van Vechten as a hustler, driven by

"a mixture of commercialism and patronizing sympathy," and treated

the novel as a quaint artifact of a less enlightened literary era: the

scribblings of a former hipster who no longer seemed very hip.

This kind of criticism turned Van

Vechten into a rather troubling figure, which is to say, a fine candidate for

reexamination, and maybe rehabilitation. In 2001, Emily Bernard published

"Remember Me to Harlem," a compendium of letters documenting the

forty year friendship between Van Vechten and Langston Hughes, who publicly

defended "Nigger Heaven," and privately enjoyed Van Vechten's roguish

sense of humor. (In one letter, Van Vechten referred to himself as "this

ole cullud man.") Two years ago, Bernard published "Carl Van Vechten

and the Harlem Renaissance" (Yale), a thoughtful reconsideration of Van

Vechten's career as both a writer and an effective champion of Negro writers.

She found much to admire in Van Vechten, though she described him as

"ensnared" in the "riddle of race." She also acknowledged

that for years she avoided teaching "Nigger Heaven" in her college

classes, so as not to subject students to "the wound that is the title of

the book."

The newest Van Vechten biographer

is Edward White, a Brit and a less agonized enthusiast. In "The

Tastemaker: Carl Van Vechten and the Birth of Modern America" (Farrar,

Straus & Giroux), White celebrates all the things that might once have

seemed shocking about Van Vechten: his conviction that Negro culture was the

essence of America; his simultaneous fascination with the avant-garde and title

broadly popular; and his string of sexual relationships with men, which were an

open secret during his life. Van Vechten's tastes were varied: his bibliography

includes an erudite cultural history of the house cat, and in his later decades

he became an accomplished portrait photographer. White calls him, plausibly

enough, the "prophet of a new cultural sensibility that promoted the

primacy of the individual, sexual freedom, and racial tolerance and dared put

the blues on a par with Beethoven." Even so, White can't help placing that

polarizing novel, and its title, at the center of his tale. Nearly a century

after he rose to fame, Van Vechten remains the white man who insisted on

publishing a pro-Negro book called "Nigger Heaven." And he will be a

tempting subject for biographers as long as there are readers who want to know

what, exactly, he was thinking.

No writer who tackles Van Vechten

can resist the urge to describe his once famous face, although none can match

the standard set by Bruce Kellner, who knew him, and who published an affectionate

biography in 1968, four years after Van Vechten's death. Kellner compares him

to a "domesticated werewolf," placid but intense, with a resting

expression that was an unnerving "blank stare," and "disfigured

by two very big and ve1y ugly protruding front teeth, like squares of broken

crockery." Van Vechten grew up in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, and, even as a boy,

he amplified these involuntary quirks with a number of voluntary ones: ascots,

slim trousers, one long fingernail. He escaped to the University of Chicago,

spending evenings at the opera and the symphony, and late nights playing piano

at the Everleigh Club, a legendary brothel or so he claimed. A good Van Vechten

biographer must also be a tireless debunker, and White, alert to his subject's

tendency toward embellishment, could find no evidence that Van Vechten had

spent time at the Everleigh's famous gold-leaf piano. "One must only be

accurate about such details in a work of fiction," Van Vechten wrote,

years later, by way of excusing his fabricated account of the historic premiere

of Stravinsky's "Le Sacre du Printemps." He hadn't been there,

either, although he had attended the second performance, which was not quite so

historic.

Van Vechten's determination always

to be in the right place - even when he wasn't - carried him to New York, to

Europe, and back to New York, a city that he found fewer and fewer reasons to

leave. After a brief marriage to a childhood friend, he wed an actress named

Fania Marinoff, who stayed with him for the rest of his life, more than half a

century, despite being given plenty of reasons to leave. Van Vechten and

Marinoff were known for their parties, which flouted the laws of Prohibition

and the norms of segregation. Starting in 1924, as Van Vechten became, in his

words, "violently interested in Negroes," the Van Vechten apartment,

on West Fifty-fifth Street, was one of the few truly integrated social spaces

in a city that wasn't as cosmopolitan as it thought it was.

Van Vechten's passion had begun as

curiosity about a novel called "The Fire in the Flint," which depicts

a Ku Klux Klan lynching in Georgia. Van Vechten arranged to meet its author, an

enterprising young N.A.A.C.P. activist named Walter White, who helped introduce

him to just about every prominent Negro singer and writer in town. In a series

of articles for Vanity Fair, Van Vechten argued that the blues deserved

"the same serious attention that has tardily been awarded to the

Spirituals," and he introduced readers to W. C. Handy, the songwriter who

popularized the blues, and to Hughes, whose poems drew inspiration from Negro

vernacular culture. Some nights, he went uptown, prowling Harlem's cabarets.

Other nights, the cabaret came to West Fifty-fifth Street, as when Bessie Smith

treated party goers to a thunderous performance. Afterward, when Marinoff

attempted to deliver a grand kiss good night, Smith threw her to the floor,

yelling, "Get the fuck away from me!" Apparently, Van Vechten was

unfazed - one attendee heard him praising Smith's performance, sotto voce, as

she was escorted out.

By the time he got to work on his

Negro novel, Van Vechten didn't feel merely like a supporter of the Harlem

Renaissance; he felt like part of it. In one telling, this feeling explains why

he thought that he could get away with his scandalous title. The novel contains

only two footnotes: one points readers to a glossary of "unusual Negro

words and phrases"; the other explains that the word "nigger" is

"freely used by Negroes among themselves," but that "its

employment by a white person is always fiercely resented." Bernard argues

that by using the word "nigger" Van Vechten sought to "establish

his privileged status" as a white man who was above the racial law. Edward

White, too, views the footnote as proof that Van Vechten saw himself as an

exceptional white man, with "special dispensation" to use language

that would otherwise be taboo. It seems just as likely, though, that Van

Vechten chose so definitive a formulation - "always fiercely

resented" - not because he thought he could escape censure but because he

knew he wouldn't. And he must have known: one of many people to whom he

revealed his title in advance was Countee Cullen, the urbane Negro poet. In his

journal, Van Vechten recorded Cullen's response: "He turns white with hurt

& I talk to him." They argued about it, and the next day they augured

some more; Cullen was never persuaded, which didn't stop Van Vechten from using

a quatrain of his as the book's epigraph. It's not hard to imagine that Van

Vechten was thinking of Cullen, and all the others who might never forgive him,

when he wrote that self-indicting footnote.

"Nigger Heaven" is a

short book, made shorter still by its standalone prologue, about a pimp known

as the Scarlet Creeper, and by its split structure, which pairs two slim

novellas, one for each protagonist. The first is given over to Mary Love, a perceptive

but anxious young librarian; the second belongs to Byron Kasson, a stubborn and

confused aspiring writer, whose brief love affair with Mary provides a hinge between

the two halves. Both characters wrestle with Negro identity: Mary is too

self-conscious to join the revelry she sees all around her in Harlem, while

Byron is paralyzed and enraged by the humiliations of a segregated city. After

a condescending white editor criticizes Byron's work, he leaves Mary and takes

up with a debauched socialite named Lasca Sartoris; when Lasca leaves him, he

descends into fury, and the novel ends with a complicated spasm of violence.

(It was Mr. Scarlet, in the night club, with the revolver though it's Byron who

faces punishment.) Van Vechten is fascinated by the diversity of Harlem, with

its "rainbow" of skin colors and its complicated hierarchy of class

and culture. When Mary rebuffs a powerful kingpin, Raymond Pettijohn, who has

cornered the market on a numbers game called bolito, the result is a bilingual

form of pulp fiction:

I'm sorry, Mr.

Pettijohn, she said, but it's no use. You see, I don't love you.

Dat doan mek no

difference, he whispered softly. Lemme mek you.

I'm afraid it's

impossible, Mary asserted more firmly.

The Bolito King

regarded her fixedly and with some wonder. You cain' mean no, he said. Ah's

willin' to wait, an' to wait some time, but Ah gotta git you. You jes' what Ah

desires.

It's impossible, Mary

repeated sternly, as she turned away.

That "throb of the

tom-tom" that David Levering Lewis detected is real enough: the sound is

described in a scene near the end, when Byron and Lasca, high on cocaine,

stumble into a demonic after-hours club. But, throughout the novel, the

character most obsessed with primal and exotic Negro identity is Mary, whose

hunger for racial authenticity becomes a cruel running joke. "She admired

all Negro characteristics and desired earnestly to possess them," we learn,

though she also suspects that this desire is self-defeating. "Unless I

acted naturally like the others, it would be no use," she thinks, and the

novel turns on the question of what it might mean for a college-educated Negro

to act "naturally"; this ongoing debate makes the novel much more

interesting than its characters or its plot.

During her brief romance with

Byron, Mary suddenly finds herself speaking the kingpin's English. "Ah'm

jes' nacherly lovin' you, mah honey," she says. To Byron, this

"nacherl" speech sounds artificial; he asks her, "Where did you

learn that delicious lingo?" And the white editor who so infuriates Byron

does it by urging him to write about Negro life in Harlem. The editor says,

"God, boy, let your characters live and breathe! Give 'em air. Let 'em

react to life and talk and act naturally." This is more or less what Van

Vechten had been telling young Negro writers in his own published essays, and

yet the character who delivers these words to Byron is more buffoon than sage:

a rude and presumptuous interloper, eager to share his dubious theories about

the happy life of the average "Negro servant-girl." Tellingly, in the

years after "Nigger Heaven" was published, Van Vechten largely

stopped offering unsolicited advice to young Negro writers. The reaction to

"Nigger Heaven" doubtless made him reticent, but so, perhaps, did the

experience of writing it.

In a brutal and influential review

published in The Crisis, the N.A.A.C.P. magazine, W. E. B. Du Bois derided

"Nigger Heaven" as "an affront to the hospitality of black folk

and to the intelligence of white"; he found nothing in its pages besides

"cheap melodrama," enlivened by bursts of "noise and

brawling." Bernard, similarly, finds the novel "banal," but celebrates

it anyway, arguing that its real contribution to the Harlem Renaissance lay in

the reviews it generated. Annoyed by Du Bois and others, a coterie of young

Negro writers joined the fight, standing up not just for Van Vechten but for

the right to fill their own pages with as much "noise and brawling"

as they pleased. Claude McKay, a Jamaican immigrant, published "Home to

Harlem," a rich and sordid tale of love and violence uptown. (After

reading it, Hughes wrote a wry letter to Van Vechten: "If yours was

'Nigger Heaven,' this is 'Nigger Hell.'") And the witty and acerbic

novelist Wallace Thurman delivered a mixed verdict on the novel itself, even as

he lambasted its critics:

In

writing "Nigger Heaven" the author wavered between sentimentality and

sophistication. That the sentimentality won out is his funeral. That the

sophistication stung certain Negroes to the quick is their funeral.

It was true that Van Vechten was

one of the patrons of Fire!!, the

celebrated single-issue magazine in which Thurman's essay appeared. But Bernard

is right to observe that, for many writers associated with the Harlem

Renaissance, the defense of "Nigger Heaven" had become an

emancipatory project. "It enabled members of the younger generation to

distinguish themselves from their predecessors," she writes. "It had

become their cackling chuckle of contempt."

No Negro writer was more caught up

in the controversy than Hughes, who was widely perceived as Van Vechten's

protege. Van Vechten had prevailed upon his friend Alfred A. Knopf to publish

Hughes's first collection, "The Weary Blues," and wrote a preface to

it. Some critics thought they detected Van Vechten's vulgarizing influence in

Hughes's earthy poems. But Van Vechten insisted, with some justification, that

"the influence, if one exists, flows from the other side." The effort

to debunk these rumors only strengthened their friendship, which endured not

only the "Nigger Heaven" controversy but also Van Vechten's withering

assessment of Hughes's pro-Soviet poems, and Van Vechten's reputational decline.

(In the nineteen-fifties, Hughes asked Van Vechten to write an introduction to

a new volume of poems, then tactfully rescinded the request after his publisher

told him that it wouldn't be a good idea.) The letters they exchanged are

affectionate and conspiratorial-in one, Van Vechten teased Hughes by telling

him that people were referring to his debut as "The Weary Blacks."

Even as the debates of the nineteen-twenties faded, Van Vechten and Hughes

liked to think of themselves as mischievous upstarts, doing battle against the

forces of Negro propriety. When Van Vechten told Hughes that he had arranged

for his papers to be archived at Yale University, Hughes feigned concern:

I was just about to

tell you about a wonderful fight that took place in Togo's Pool Room in Monterey

the other day in which various were cut from here to yonder and the lady who

used to be the second wife of Noel's valet who came to New York with him that

time succeeded in slicing several herself - but you know the Race would come

out here and cut me if they knew I was relaying such news to posterity via the

Yale Library. So now how can I tell you?

If Van Vechten's attraction to men

was an open secret, Hughes's romantic life was a secret secret; his biographer

Arnold Rampersad is one of many historians who have looked for evidence and

come away with nothing conclusive. White, considering the close relationship

between Hughes and Van Vechten, concludes that they were not lovers; as proof,

he offers their correspondence, which he contrasts to the "flirtatious"

letters, rife with "homosexual coding and innuendo," that Van Vechten

sent to his male lovers. "His letters to Hughes feature none of

that," White argues, "and disclose nothing but warm, jovial

friendship and honest exchanges of opinions." It might be said, though,

that Van Vechten's version of "jovial friendship" wasn't entirely

free of sexual suggestion. One of Van Vechten's missives, from 1943, includes

an out-of context postscript: "I have just photographed an extremely

beautiful merchant seaman (cullud) age 21 who used to be an undertaker and is

devoted to the arts." The next year, he told Hughes about a "Best

Built Man" competition he had attended in Harlem. 'The Adonises (white and

cullud) are obliged to POSE to display their muscles and some of the attitudes

were honeys," Van Vechten wrote.

Despite his reputation for lurid

prose, Van Vechten could be surprisingly discreet, and, even with the benefit

of thousands of letters and journal entries, there are parts of his life that

are hard to reconstruct. Early notes make reference to a turbulent marriage.

(From 1925: "I get drunk & get rough with Marinoff.") Later,

there are passing, references to estrangements and vacations and

reconciliations, and also to men who turn out to have been Van Vechten's

lovers. Sometimes, in his letters to his wife, he writes as if he were

travelling or dining solo, when he wasn't; other times, the men are mentioned

casually, as mutual friends.

White, lacking details, has few

stories to tell, but he confidently diagnoses Marinoff's plight. "In New

York, where Van Vechten's coterie of young men was always buzzing around him,

she often felt as if she had to wait in line for an audience with her

husband," he writes. Occasionally, he allows himself to express some

frustration that his subject wasn't more forthright; when it came to the

"sexual freedom" that White wants to celebrate, Van Vechten declined

to preach what he practiced. One of Van Vechten's closest friends and lovers

was Mark Lutz, a journalist from Virginia, who died in 1967. Van Vechten sent

him thousands of letters in the course of more than three decades, but after

Lutz's death those letters were destroyed, in accordance with his wishes.

Above all, Van Vechten seems to

have been careful to keep his two lives separate. The Harlem Renaissance was,

in Henry Louis Gates's formulation, "surely as gay as it was black,"

and Bernard counts Van Vechten among the many "gay downtown whites who

went uptown in search of sexual recreation." But although "Nigger

Heaven" includes an entry in its glossary for 'jig-chaser' ("a white

person who seeks the company of Negroes") and its counterpart,

"pinkchaser," the book's acknowledgment of same-sex encounters

consists of a single reference to a bar known for its "bull-dikers."

Perhaps Van Vechten felt that his Negro literary project would be immeasurably

more difficult if he were widely perceived to have ulterior motives. Richard

Bruce Nugent, the first black writer to produce frank descriptions of same-sex

desire, remembered an odd exchange with Van Vechten, later in his life. At a

party, he touched Nugent's shoulder and said, "If you had just patted me

on the head and said, 'Carl, you're a nice boy,' you could have had anything

you wanted." But, to Nugent, this seemed less like a proposition and more

like an older man's plea for acknowledgment.

The most startling thing about

White's book is its breadth: "Nigger Heaven" was merely one episode

in a very long and very episodic life. Van Vechten remained a devoted friend

and champion of Stein, and after her death, in 1946, he became her literary

executor. (A collection of their letters was published last summer; it's nine

hundred and one pages long.) He was celebrated, in retrospect, as one of

America's first major dance critics, and one of the first music critics to

embrace the sounds of the twentieth century. When he took up photography, he

badgered and flattered a wide range of luminaries into sitting for him, from

Joe Louis to William Faulkner; he captured some of the best-known images we

have of Stein, Bessie Smith, and Billie Holiday. He never quite broke into

Hollywood, but he tried. Despite these other interests, he played an outsized

role in the development of Negro music and literature, which is partly a

tribute to how isolated and powerless black artists were in those days. One

well-connected white man could alter the course of a movement, just by writing

some articles and making some introductions. This, of course, was precisely what

Du Bois found so dismaying.

Back in the nineteen-twenties, Van

Vechten sometimes portrayed himself as a dilettante, whose interest in Negro

culture was just a phase. In a letter to H. L. Mencken, in 1925, he wrote,

"Jazz, the blues, Negro spirituals, all stimulate me enormously for the

moment. Doubtless, I shall discard them too in time." Of course, he never

did-in this and other ways, he was far more loyal and earnest than he sometimes

pretended to be. Much as he loved photography, his true life's work was the

Yale Library archive, and he pestered his old friend Hughes with endless

requests for material to add to the historical record. In 1963, a year before

Van Vechten's death, a reporter from The

New Yorker went to visit him at his apartment; he had moved from West

Fifty-fifth Street to Central Park West, but his interests hadn't changed. He

showed off some recent photographs, held forth on his favorite foods, shared

his enthusiasm for foreign films, and bragged about the friends he still had in

Harlem. "I still get about twenty-five letters a day from Negroes,"

he said. He never had children, although White raises the possibility of one or

more secret births and quiet adoptions. His life was his obsessions, which is

why he held them so tight - he was, in the end, the opposite of a dilettante.

He said, "I don't think I've ever lost interest in anything."

New Yorker

magazine, Feb 17 & 24, 2014

Wednesday, September 16, 2015

Don't Be Like That

by Kelefa Sanneh

Does black culture need to be reformed?

It was just after eight o'clock on

a November night when Robert McCulloch, the prosecuting attorney for St. Louis

County, announced that a grand jury would not be returning an indictment in the

police killing of Michael Brown, who was eighteen, unarmed, and

African-American. About an hour later and eight hundred miles away, President

Obama delivered a short and sober speech designed to function as an

anti-inflammatory. He praised police officers while urging them to "show

care and restraint" when confronting protesters. He said that

"communities of color" had "real issues" with law

enforcement, but reminded disappointed Missourians that Brown's mother and

father had asked for peace. "Michael Brown's parents have lost more than

anyone," he said. "We should be honoring their wishes."

Even as he mentioned Brown's

parents, Obama was careful not to invoke Brown himself, who had become a

polarizing figure. To the protesters who chanted, "Hands up! Don't

shoot!," Brown was a symbol of the young African-American man as victim-

the chant referred to the claim that Brown was surrendering, with his hands up,

when he was killed. Critics of the protest movement were more likely to bring

up the video, taken in the fifteen minutes before Brown's death, that appeared

to show him stealing cigarillos from a convenience store and then shoving and

intimidating the worker who tried to stop him-the victim was also, it seemed, a

perpetrator.

After the Times described Brown as

"no angel," the MSNBC host Melissa Harris-Perry accused the newspaper

of "victim-blaming," arguing that African- Americans, no matter how

"angelic," will never be safe from "those who see their very

skin as a sin." But, on the National Review Web site, Heather MacDonald

quoted an anonymous black corporate executive who told her, "Michael Brown

may have been shot by the cop, but he was killed by parents and a community

that produced such a thug." And so the Michael Brown debate became a proxy

for our ongoing argument about race: where some seek to expose what America is

doing to black communities, others insist that the real problem is what black

communities are doing to themselves.

Sociologists who study black

America have a name for these camps: those who emphasize the role of

institutional racism and economic circumstances are known as structuralists,

while those who emphasize the importance of self-perpetuating norms and

behaviors are known as culturalists. Mainstream politicians are culturalists by

nature, because in America you seldom lose an election by talking up the

virtues of hard work and good conduct. But in many sociology departments

structuralism holds sway-no one who studies African-American communities wants

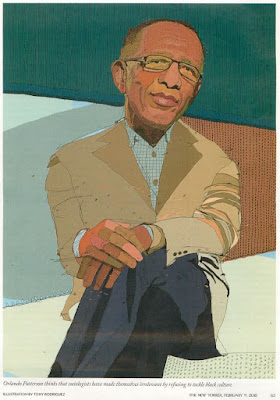

to be accused, as the Times was, of "victim-blaming." Orlando

Patterson, a Jamaica-born sociologist at Harvard with an appetite for

intellectual combat, wants to redeem the culturalist tradition, thereby

redeeming sociology itself. In a manifesto published in December, in the

Chronicle of Higher Education, he argued that "fearful" sociologists

had abandoned "studies of the cultural dimensions of poverty, particularly

black poverty," and that the discipline had become "largely

irrelevant." Now Patterson and Ethan Fosse, a Harvard doctoral student in

sociology, are publishing an ambitious new anthology called "The

Cultural Matrix: Understanding Black Youth" (Harvard), which is

meant to show that the culturalist tradition still has something to teach us.

The book arrives on the fiftieth

anniversary of its most important predecessor: a slim government report written

by an Assistant Secretary of Labor and first printed in an edition of a

hundred. The author was Daniel Patrick Moynil1an, and the title was "The

Negro Family: The Case for National Action." At first, the historian James

T. Patterson has written, only one copy was allowed to circulate; the other

ninety-nine were locked in a vault. Moynihan's report cited sociologists and

government surveys to underscore a message meant to startle: the Negro

community was doing badly, and its condition was probably "getting worse,

not better." Moynihan, who was trained in sociology, judged that

"most Negro youth are in danger of being caught up in the tangle of

pathology that affects their world, and probably a majority are so

entrapped." He returned again and again to his main theme, "the

deterioration of the Negro family," which he considered "the

fundamental source of the weakness of the Negro community"; he included a

chart showing the rising proportion of nonwhite births in America that were

"illegitimate." (The report used the terms "Negro" and

"nonwhite" interchangeably.) And, at the end, Moynihan called-

briefly, and vaguely- for a national program to "strengthen the Negro

family."

The 1965 report was leaked to the

press, inspiring a series of lurid articles, and later that year the Johnson

Administration released the entire document, making it available for forty-five

cents. Moynihan found some allies, including Martin Luther King, Jr. ln a

speech in October, King referred to an unnamed "recent study" showing

that "the Negro family in the urban ghettos is crumbling and

disintegrating." But King also worried that some people might attribute

this "social catastrophe" to "innate Negro weaknesses," and

that discussions of it could be "used to justify neglect and rationalize

oppression." Many sociologists were harsher. Andrew Billingsley argued

that in assessing the problems caused by dysfunctional black families Moynihan

had mistaken the symptom for the sickness. "The family is a creature of

society," he wrote. ''And the greatest problems facing black families are

problems which emanate from the white racist, militarist, materialistic society

which places higher priority on putting white men on the moon than putting

black men on their feet on this earth." This debate had influence far beyond

sociological journals: when Harris-Perry accused the Times of

"victim-blaming," she was using a term coined by the psychologist

William Ryan, in a book-length rebuttal to the Moynihan report, "Blaming

the Victim."

Orlando Patterson thinks that, half

a century later, it's easier to appreciate all that Moynihan got right.

"History has been kind to Moynihan," he and Fosse write, which might

be another way of saying that history has not been particularly kind to the

people Moynihan wrote about-some of his dire predictions no longer seem so

outlandish. Moynihan despaired that the illegitimacy rate for Negro babies was

approaching twenty-five per cent. According to the Centers for Disease Control

and Prevention, the equivalent rate in 2013 was 71.5 per cent. (The rate for

non-Hispanic white babies was 29.3 per cent.) Even so, Patterson and the other

contributors avoid pronouncing upon "ghetto culture" or "the

culture of poverty," or even "black culture." Instead, the

authors see shifting patterns of belief and behavior that may nevertheless

combine to make certain families less stable, or certain young people less

employable. The hope is that, by paying close attention to culture,

sociologists will be better equipped to identify these patterns, and help change

them.

In Moynihan's view, the triumph of

the civil-rights movement made his report that much more exigent: he was sure

that as long as the Negro family was unstable the movement's promises of

economic advancement and social equality would remain unfulfilled. Of course,

alarming reports about the state of black culture have a long history in

America: sometimes the accounts of deviant behavior were meant to explain why

black oppression was justified; at other times, the accounts were meant to

explain why black oppression was harmful.

In 1899, the trailblazing Negro

scholar W.E.B. Du Bois drew on interviews and census data to produce "The

Philadelphia Negro: A Social Study," which helped shape the young

discipline of sociology. Du Bois spent a year living in the neighborhood he

wrote about, amid what he later described as "an atmosphere of dirt,

drunkenness, poverty, and crime." What emerged from this field research

was a stem, unsentimental book; at times, Du Bois's disdain for his subjects,

especially what he called "the dregs," seemed as great as his outrage

at the discrimination they faced. He observed, in language much harsher than

Moynihan's, the large number of unmarried mothers, many of whom he

characterized as "ignorant and loose. "In this book, as in the rest

of his life, Du Bois did not shy away from prescription. He concluded by

reminding whites of their duty to stop employment discrimination, which he

called "morally wrong, politically dangerous, industrially wasteful, and

socially silly. "But he reminded Negro readers that they had a duty, too:

to work harder, to behave better, and to stem the tide of "Negro

crime," which was, he said, "a menace to a civilized people."

His chapter on "The Negro Criminal," illustrated with charts and

graphs, showed that Negroes were disproportionately represented in police

records though he suggested that the police, too, were acting

disproportionately.

In the years before Moynihan, other

social scientists refined Du Bois's approach, most famously Oscar Lewis, who

used the term "culture of poverty" to describe what he saw among the

Mexican families he studied. In retrospect, it seems clear that what infuriated

many of Moynihan's readers wasn't so much what he wrote (he was mainly

summarizing contemporary research) as what he represented. He was a young white

political staffer explaining what was wrong with black communities, so he had

to be wrong, even if he was right. One of the most revealing and representative

responses came from James Farmer, the director of the Congress of Racial

Equality: "We are sick unto death of being analyzed, mesmerized, bought,

sold, and slobbered over, while the same evils that are the ingredients of our

oppression go unattended." Moynihan had stumbled into a quandary familiar

to sociologists: sometimes your subject doesn't want to be subjectified.

The battle over Moynihan's report

was a battle over the legacy of slavery, too, and Orlando Patterson was well

qualified to join it. He earned his Ph.D. in 1965, with a dissertation on the

sociology of Jamaican slavery, and in his best-known books, "Slavery and

Social Death" and "Freedom in the Making of Western Culture," he

broadened his focus to consider the institution of slavery and how it gave rise

to the ideal of freedom. (He has also published a trio of novels set in

Jamaica.) In 1973, as the anti-Moynihan wave was cresting, Patterson offered a

partial defense: rebutting Ryan's rebuttal, he wrote that writers like Moynihan

"in no way blame the victim." In fact, Patterson argued, Moynihan's

report was overly "deterministic," portraying black Americans as the

inevitable victims of a long and oppressive history. Even more than Du Bois,

Moynihan stressed the debilitating legacy of American slavery, asserting that

it was "indescribably worse" than any form of bondage in the history

of the world. Although Moynihan's fiercest critics didn't dispute this, they

found themselves arguing that slavery had been less destructive than Moynihan

thought: they celebrated the resilience of the black family in its non-standard

forms . (Moynihan's "illegitimacy" statistics couldn't account for

the grandparents and other extended-family members who might help a mother

bring up her child.) Patterson called these scholars "survivalists,"

in contrast to "catastrophists," and years later the survivalists'

work can seem too transparent in its aims. A number of sociologists, wary of

insulting their subjects, seemed content to settle for flattery instead,

depicting the black family as an extraordinary success story, no matter what

the statistics said.

Patterson sometimes implies that

the Moynihan affair chastened sociology forever, but the culturalist impulse

didn't go away. In 1978, William Julius Wilson popularized the term

"underclass," to describe the non-working poor who have been left

behind by the disappearance of blue-collar jobs, but he also came to believe

that "social isolation" helps create ways of living that perpetuate

poverty. (Wil- . son argued that declining professional prospects made some

black men less marriageable. Patterson thinks that declining marriage rates had

more to do with the increased availability of contraception and abortion, which

eroded cultural norms that had once compelled men to marry the women they

impregnated.) And in 1999, on the hundredth anniversary of Du Bois's classic,

Elijah Anderson published a new sociological study of poor black neighborhoods

in Philadelphia, "Code of the Street," which took seriously its

informants' own characterization of themselves and their neighbors as either

"decent" or "street" or, not infrequently, a bit of both.

In "The Cultural Matrix," Patterson updates and expands Anderson's

taxonomy, listing "three main social groups" (the middle class, the

working class, and "disconnected street people") that are common in

"disadvantaged" African-American neighborhoods, along with "four

focal cultural configurations" (adapted mainstream, proletarian, street,

and hip-hop). In general, though, "black youth" means "poor

black youth;" since poverty is what gives a project such as this one its

urgency.

The contributors to "The

Cultural Matrix" strive to avoid technical language, in what seems to be a

brave but doomed attempt to attract casual readers to a book that is nearly

seven hundred pages long. Some of the best cultural sociology draws its power

from careful interviewing and observation. Anderson's "Code of the

Street" was influential because it was widely read, and it was widely read

because it often resembled a novel, full of complicated people and pungent

testimonials. (One "decent" woman's account of raising five children

had a nine-word opening sentence that no writing workshop could have improved:

"My son that's bad now-his name is Curtis.") Some of Patterson's

contributors have a similar facility with anecdote. A chapter about resisting

the influence of poor neighborhoods includes a startling detail about a tough

but crime-averse young man named Gary: "He pats people down before they

get in his car to make sure they are not carrying anything that could get him

arrested. "This, apparently, is what staying out of trouble might entail

for a young black man in Baltimore.

Among the most important essays in

the new anthology is Jody Miller's account of sexual relationships in St.

Louis. An eighteen-year-old informant named Terence talks about participating

in a sexual encounter that may not have been consensual, and his affectless

language only makes the scene more discomfiting:

INTERVIEWER: Did you know the girl?

TERENCE: Naw, I ain't know her, know her like for real know her. But I knew her name or whatever. I had seen her before. That was it though.

INTERVIEWER: So when you all got there, she was in the room already?

TERENCE: Naw, when we got there, she hadn't even got there yet. And when she came, she went in the room with my friend, the one she had already knew. And then after they was in there for a minute, he came out and let us know that she was gon', you know, run a train or whatever. So after that, we just went one by one.

Miller knows that most readers will find this appalling, so she follows Terence's testimony with an assurance that incidents such as these reflect a legacy of racism-she mentions, for instance, "the gross 'scientific' objectification of African women in the nineteenth century." This is a common technique among the new culturalists: every distressing contemporary phenomenon must be matched to an explicitly racist antecedent, however distant. This distance is what separates the culturalists from the structuralists. Patterson and the others are right that cultural traits often outgrow and outlive the circumstances of their creation. But often what remains is a circular explanation, description masquerading as a causal account. African-American gender relations are troubled because of "cultural features" that foster troubled gender relations.

One difference between the current

era and Moynihan's, or Du Bois's, is that contemporary sociologists have a new

potential culprit to blame for the disorder they see: hip-hop. The anthology

includes a careful history of the genre by Wayne Marshall, an

ethnomusicologist, who emphasizes its mutability. But Patterson, brave as ever,

can't resist wading into this culture war. In one exuberant passage, he

compares MC Hammer to Nietzsche, uses an obscure remix verse to contend that

hip-hop routinely celebrates "forced abortions," and pronounces Lil

Wayne "irredeemably vulgar" and "all too typical" of the

genre's devolution. And yet he is a conscientious enough social scientist to

concede that there doesn't seem to be decisive evidence for a "causal

link" between violent lyrics and violent behavior. Writing in 1999, Anderson

mentioned hip-hop only in passing, suggesting that it supported, and was

supported by, "an ideology of alienation." (He was nearly as critical

of "popular love songs" and "television soap operas, "which

he judged to nourish girls' dreams of storybook romance. "When a girl is

approached by a boy," he wrote, "her faith in the dream clouds her

view of the situation.") Now hiphop has achieved cultural hegemony, but

Patterson doesn't seem to have noticed that the genre has become markedly less

pugnacious in recent years, thanks to non-thuggish stars like Drake, Nicki

Minaj, Macklemore, Kendrick Lamar, and Iggy Azalea. The next wave of

culturalist analyses will surely be able to explain how this music, too, is

part of the problem.

The most provocative chapter in

"The Cultural Matrix" is the final one, an exacting polemic by a

Harvard colleague of Patterson's, Tommie Shelby, a professor of African and

African-American studies and of philosophy. Shelby accepts, for the sake of

argument, the idea that "suboptimal cultural traits" are the major

impediment for many African- Americans seeking to escape poverty. He notes, in

language much more delicate than Moynihan's (let alone Du Bois's), that "some

in ghetto communities are believed to devalue traditional co-parenting and to

eschew mainstream styles of childrearing." Still, Shelby is suspicious of

attempts to reform these traits, and not only because he is wary of "victim-blaming."

He thinks that the "ghetto poor" have a right to remain defiantly

unaltered. In his view, a program of compulsory cultural reform "robs the

ghetto poor of a choice that should be theirs alone-namely, whether the

improved prospects for ending or ameliorating ghetto poverty are worth the loss

of moral pride they would incur by conceding the insulting view that they have

not shown themselves to be deserving of better treatment." For Shelby,

opposing hypothetical future government programs is also a way of registering frustration

with past government action, and inaction. "Given its failure to secure

just social conditions," he writes, "the state lacks the moral

standing to act as an agent of moral reform."

This "moral standing"

argument is too powerful for its own good, because it would invalidate just

about everything done by the U.S. government, or any other. The crucial question

is not whether the state has the "moral standing" to reform cultural

practices in the ghetto but whether it has the ability. Politicians love to

call for such reform; Obama could have been channeling Moynihan when he said,

in his famous 2008 speech on race, that African- Americans needed to take more

responsibility for their own communities by "demanding more from our

fathers." But a demand is not a program. Patterson, in the essay for the

Chronicle, suggested that "cultural values, norms, beliefs, and habitual

practices may be easier to change than structural ones." And yet a chapter

in the anthology, about a federal relationship-counselling program called

Building Strong Families, provides less reason for confidence. In most cases,

the follow-up reports suggested that the program had little or no effect on

tl1e relationships it sought to help; in one city, Baltimore, couples who

received counselling were markedly more likely to split. (The authors, looking

for good news, voice a faint hope that the demise of those relationships

"may lead to better repartnering outcomes.")

A few years ago, in The Nation,

Patterson responded to some disappointing statistics showing high unemployment

and persistent segregation by urging African-Americans to "do some serious

soul-searching." But part of the problem with calls for cultural reform is

that the so-called "ghetto poor" tend to agree with the kinds of messages

that outsiders, whether tough-love politicians or self-conscious sociologists

alike, would urge upon them: work matters, family matters, culture matters.

Ethan Fosse draws on a number of recent surveys of tl1e

"disconnected"-the term refers to young people who are neither

employed nor attending school and finds that they adhere more strongly to

various mainstream cultural values than their connected counterparts do: they

are more likely to say that having a good career is "very important"

to them, and seventy-four per cent of them say that black men "don't take

their education seriously enough," compared with only sixty-two per cent

of connected black youth. Surveys also suggest that disconnected young people

are more likely to agree with Patterson's critique of hip-hop- the people most

susceptible to the genre's influence turn out to be the ones most skeptical of

it. In an overview chapter, Patterson wryly notes that results such as these

may pose a conundrum. "Sociologists love subjects who tell truth to

mainstream power," he writes. "They grow uncomfortable when these

subjects tell mainstream truths to sociologists. "But none of this offers

encouragement for people who think that cultural change is a key to social

uplift.

Just how dire is the situation?

Moynihan worried that "the Negro community" was in a state of

decline, bedevilled by an increasingly matriarch al family structure, which led

to the increasing incidence of crime and delinquency. Much of Moynihan's

historical data was scant or inconclusive, but, when it came to violent crime,

he guessed correctly: in the fifteen years after he published his report, the

country's homicide rate doubled, with blacks over represented among both

perpetrators and victims. America, and Negro America in particular, was at the

beginning of a years-long catastrophe. But what happened next was even more

surprising: beginning in the early nineteen-nineties, the homicide rate, like

other rates of violent crime, began to decline; today, African-Americans are

about half as likely to be involved in a homicide, either as perpetrator or as

victim, as they were two decades ago. Patterson and Fosse write that, in the

years after Moynihan's report, a "discrepancy" developed between the

optimistic scholarship of sociologists, eager to emphasize the resilience of

black families, and "the reality of urban black life," which was

increasingly grim. But the contemporary era has been marked by the opposite

discrepancy: even as the new culturalists were restirrecting Moynihan's diagnosis,

the scourge of crime was in retreat.

Patterson, committed to his

critique of African-American cultural life, can't bring himself to celebrate

this news. Hiphop is important to him because it fuels his suspicion that,

despite the drop in crime, black culture is in trouble. Fosse seems to share

this pessimism, reporting "an alarming increase in the percentage of black

youth who are structurally disconnected over the past decade. "He uses

survey data to create a fitted curve, showing that "nearly 25 percent"

ofblack youth were disconnected in 2012, while the white rate "has

remained below 15 percent." (The curve is not included in the book.) In

fact, the data suggest that percentages of disconnection among black and white

youth have been rising at about the same rate over the past decade; what's most

alarming is not the recent increase but the ongoing disparity. Among Patterson,

Fosse, and their peers, the ten.dency to write as if black culture were in

exceptional crisis seems to be what a sociologist might call an unexamined

injunctive norm: a shared prescriptive rule, one so ingrained that its

followers don't even realize it exists.

And so the good news on crime gets

downplayed. "By focusing too much on the sharp oscillation period between

the eighties and late nineties," Patterson writes, "social scientists

working on crime run the risk of neglecting the historic pattern of high crime

rates among blacks. "But this hardly justifies the fact that these

sociologists, otherwise so concerned with the effects of crime and the

criminal-justice system, aren't more interested in this extraordinary rise and

fall, which defied Moynihan's suggestion that crime and

"illegitimacy" were inextricably linked. Apparently, this great

oscillation neither required nor induced any great changes in black culture,

and it has inspired nothing like a consensus among criminologists looking for a

cause. Fine-grained cultural trends and well-meaning cultural initiatives often

seem insignificant compared with the mysterious forces that can stealthily

double or halve the violent-crime rate in the course of a decade or two. A

chapter on "street violence" mentions the homicide drop only in

passing, in its final paragraph.

In our political debates, as in

cultural sociology, it can take some time for the stories to catch up to the

statistics, especially because it takes a while to decipher what the statistics

are saying. There is some evidence that, after years of rapid expansion, the

African-American prison population levelled off, and may even have begun to

decrease. But that hasn't made the recent arguments over race and the

criminal-justice system any less urgent. The outrage in Missouri was followed,

a week later, by outrage in New York, when a Staten Island grand jury declined

to indict a white police officer who caused the death of an unarmed

African-American man. In the aftermath, as some other commentators talked about

America's legacy of racism, Patterson dissented. In a Slate interview, he said,

"I am not in favor of a national conversation on race." He said that

most white people in America had come to accept racial equality, but added that

"there's a hard core of about twenty per cent which still remains

thoroughly racist." The startling implication is that, even now, blacks in

America live alongside an equal number of "thoroughly racist" whites.

If this is true, it may explain the tragic sensibility that haunts Patterson's

avowedly optimistic approach to race in America. He contends that black culture

can and must change while conceding, less loudly, that "thoroughly

racist" whites are likely to remain stubbornly the same.

There is a paradox at the heart of

cultural sociology, which both seeks to explain behavior in broad, categorical

terms and promises to respect its subjects' autonomy and intelligence. The

results can be deflating, as the researchers find that their subjects are not

stupid or crazy or heroic or transcendent-their cultural traditions just don't

seem peculiar enough to answer the questions that motivate the research. Black

cultural sociology has always been a project of comparison: the idea is not

simply to understand black culture but to understand how it differs from white

culture, as part of the broader push to reduce racial disparities that have

changed surprisingly little since Du Bois's time. Fifty years after Moynihan's

report, it's easy to understand why he was concerned. Even so, it's getting

easier, too, to sympathize with his detractors, who couldn't understand why he

thought new trends might explain old problems. If we want to learn more about

black culture, we should study it. But, if we seek to answer the question of

racial inequality in America, black culture won't tell us what we want to know.

New Yorker

magazine, February 9, 2015.

COLLEGE CALCULUS by John Cassidy

What’s the real value of higher education? As the supply of college grads expands, many are taking jobs that shouldn’t require a degree.

What’s the real value of higher education? As the supply of college grads expands, many are taking jobs that shouldn’t require a degree.

If there is one thing most

Americans have been able to agree on over the years, it is that getting an

education, particularly a college education, is a key to human betterment and

prosperity. The consensus dates back at least to 1636, when the legislature of

the Massachusetts Bay Colony established Harvard College as America's first institution

of higher learning. It extended through the establishment of "land grant

colleges" during and after the Civil War, the passage of the G.I. Bill

during the Second World War, the expansion of federal funding for higher

education during the Great Society era, and President Obama's efforts to make

college more affordable. Already, the cost of higher education has become a big

issue in the 2016 Presidential campaign. Three Democratic candidates-Hillary

Clinton, Martin O'Malley, and Bernie Sanders- have offered plans to reform the

student-loan program and make college more accessible.

Promoters of higher education have

long emphasized its role in meeting civic needs. The Puritans who established

Harvard were concerned about a shortage of clergy; during the Progressive Era, John

Dewey insisted that a proper education would make people better citizens, with

enlarged moral imaginations. Recently, as wage stagnation and rising inequality

have emerged as serious problems, the economic arguments for higher education

have come to the fore. "Earning a post-secondary degree or credential is

no longer just a pathway to opportunity for a talented few," the White

House Web site states. "Rather, it is a prerequisite for the growing jobs

of the new economy." Commentators and academic economists have claimed

that college doesn't merely help individuals get higher-paying jobs; it raises

wages throughout the economy and helps ameliorate rising inequality. In an

influential 2008 book, "The Race Between Education and Technology,"

the Harvard economists Claudia Goldin and Lawrence F. Katz argued that

technological progress has dramatically increased the demand for skilled

workers, and that, in recent decades, the American educational system has

failed to meet the challenge by supplying enough graduates who can carry out

the tasks that a high-tech economy requires. "Not so long ago, the

American economy grew rapidly and wages grew in tandem, with education playing

a large, positive role in both," they wrote in a subsequent paper.

"The challenge now is to revitalize education-based mobility."

The "message from the media,

from the business community, and even from many parts of the government has

been that a college degree is more important than ever in order to have a good

career," Peter Cappelli, a professor of management at Wharton, notes in

his informative and refreshingly skeptical new book, "Will College Pay

Off?" (Public Affairs). "As a result, families feel even more

pressure to send their kids to college. This is at a time when more families

find those costs to be a serious burden. "During recent decades, tuition

and other charges have risen sharply-many colleges charge more than fifty

thousand dollars a year in tuition and fees. Even if you factor in the

expansion of financial aid, Cappelli reports, "students in the United

States pay about four times more than their peers in countries elsewhere."

Despite the increasing costs-and

the claims about a shortage of college graduates-the number of people attending

and graduating from four-year educational institutions keeps going up. In the

2000-01 academic year, American colleges awarded almost 1.3 million bachelor's

degrees. A decade later, the figure had jumped nearly forty per cent, to more

than 1.7 million. About seventy per cent of all high-school graduates now go on

to college, and half of all Americans between the ages of twenty-five and

thirty-four have a college degree. That's a big change. In 1980, only one in

six Americans twenty-five and older were college graduates. Fifty years ago, it

was fewer than one in ten. To cater to all the new students, colleges keep

expanding and adding courses, many of them vocationally inclined. At Kansas

State, undergraduates can major in Bakery Science and Management or Wildlife

and Outdoor Enterprise Management. They can minor in Unmanned Aircraft Systems

or Pet Food Science. Oklahoma State offers a degree in Fire Protection and

Safety Engineering and Technology. At Utica College, you can major in Economic

Crime Detection.

In the fast-growing for-profit

college sector, which now accounts for more than ten per cent of all students,

vocational degrees are the norm. De Vry University- which last year taught more

than sixty thousand students, at more than seventy-five campuses--offers majors

in everything from multimedia design and development to health-care

administration. On its Web site, De Vry boasts, "In 2013, 90% of DeVry

University associate and bachelor's degree grads actively seeking employment

had careers in their field within six months of graduation." That sounds

impressive-until you notice that the figure includes those graduates who had

jobs in their field before graduation. (Many DeVry students are working adults

who attend college part-time to further their careers.) Nor is the phrase

"in their field" clearly defined. "Would you be okay rolling the

dice on a degree in communications based on information like that?"

Cappelli writes. He notes that research by the nonprofit National Association

of Colleges and Employers found that, in the same year, just 6.5 per cent of

graduates with communications degrees were offered jobs in the field. It may be

unfair to single out DeVry, which is one of the more reputable for-profit

education providers. But the example illustrates Cappelli's larger point: many

of the claims that are made about higher education don't stand up to scrutiny.

"It is certainly true that

college has been life changing for most people and a tremendous financial

investment for many of them," Cappelli writes. "It is also true that

for some people, it has been financially crippling .... The world of college

education is different now than it was a generation ago, when many of the

people driving policy decisions on education went to college, and the

theoretical ideas about why college should pay off do not comport well with the

reality."

No idea has had more influence on

education policy than the notion that colleges teach their students specific,

marketable skills, which they can use to get a good job. Economists refer to

this as the "human capital" theory of education, and for the past

twenty or thirty years it has gone largely unchallenged. If you've completed a

two-year associate's degree, you've got more "human capital" than a

high-school graduate. And if you've completed a four-year bachelor's degree

you've got more "human capital" than someone who attended a community

college. Once you enter the labor market, the theory says, you will be rewarded

with a better job, brighter career prospects, and higher wages.

There's no doubt that college

graduates earn more money, on average, than people who don't have a degree. And

for many years the so-called "college wage premium'' grew. In 1970,

according to a recent study by researchers at the Federal Reserve Bank of New

York, people with a bachelor's degree earned about sixty thousand dollars a

year, on average, and people with a high-school diploma earned about forty-five

thousand dollars. Thirty-five years later, in 2005, the average earnings of

college graduates had risen to more than seventy thousand dollars, while

high-school graduates had seen their earnings fall slightly. (All these figures

are inflation-adjusted.) The fact that the college wage premium went up at a

time when the supply of graduates was expanding significantly seemed to confirm

the Goldin-Katz theory that technological change was creating an

ever-increasing demand for workers with a lot of human capital. During the past

decade or so, however, a number of things have happened that don't easily mesh

with that theory. If college graduates remain in short supply, their wages

should still be rising. But they aren't. In 2001, according to the Employment

Policy Institute, a liberal think tank in Washington, workers with

undergraduate degrees (but not graduate degrees) earned, on average, $30.05 an

hour; last year, they earned $29.55 an hour. Other sources show even more

dramatic falls. "Between 2001 and 2013, the average wage of workers with a

bachelor's degree declined 10.3 percent, and the average wage of those with an

associate's degree declined 11.1 percent," the New York Fed reported in

its study. Wages have been falling most steeply of all among newly minted

college graduates. And jobless rates have been rising. In 2007, 5.5 per cent of

college graduates under the age of twenty-five were out of work. Today, the

figure is close to nine per cent. If getting a bachelor's degree is meant to

guarantee entry to an arena in which jobs are plentiful and wages rise

steadily, the education system has been failing for some time.

And, while college graduates are

still doing a lot better than non-graduates, some studies show that the

earnings gap has stopped growing. The figures need careful parsing. If you lump

college graduates in with people with advanced degrees, the picture looks

brighter. But almost all the recent gains have gone to folks with graduate

degrees. "The four year- degree premium has remained flat over the past

decade," the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland reported. And one of the

main reasons it went up in the first place wasn't that college graduates were

enjoying significantly higher wages. It was that the earnings of non-graduates

were falling.

Many students and their families

extend themselves to pay for a college education out of fear of falling into

the low-wage economy. That's perfectly understandable. But how sound an

investment is it? One way to figure this out is to treat a college degree like

a stock or a bond and compare the cost of obtaining one with the accumulated

returns that it generates over the years. (In this case, the returns come in

the form of wages over and above those earned by people who don't hold

degrees.) When the research firm PayScale did this a few years ago, it found

that the average inflation- adjusted return on a college education is about

seven per cent, which is a bit lower than the historical rate of return on the

stock market. Cappelli cites this study along with one from the Hamilton

Project, a Washington-based research group that came up with a much higher

figure-about fifteen per cent but by assuming, for example, that all college

students graduate in four years. (In fact, the four-year graduation rate for

full-time, first-degree students is less than forty per cent, and the six-year

graduation rate is less than sixty per cent.)

These types of studies, and there

are lots of them, usually find that the financial benefits of getting a college

degree are much larger than the financial costs. But Cappelli points out that

for parents and students the average figures may not mean much, because they

disguise enormous differences in outcomes from school to school. He cites a

survey, carried out by PayScale for Businessweek in 2012, that showed that

students who attend M.I.T., Caltech, and Harvey Mudd College enjoy an annual

return of more than ten per cent on their "investment." But the

survey also found almost two hundred colleges where students, on average, never

fully recouped the costs of their education. "The big news about the

payoff from college should be the incredible variation in it across

colleges," Cappelli writes. "Looking at the actual return on the

costs of attending college, careful analyses suggest that the payoff from many

college programs-as much as one in four- is actually negative. Incredibly, the

schools seem to add nothing to the market value of the students."

So what purpose does college really

serve for students and employers? Before the human-capital theory became so

popular, there was another view of higher education-as, in part, a filter, or

screening device, that sorted individuals according to their aptitudes and

conveyed this information to businesses and other hiring institutions. By

completing a four-year degree, students could signal to potential employers

that they had a certain level of cognitive competence and could carry out

assigned tasks and work in a group setting. But a college education didn't

necessarily imbue students with specific work skills that employers needed, or

make them more productive.

Kenneth Arrow, one of the giants of

twentieth-century economics, came up with this account, and if you take it

seriously you can't assume that it's always a good thing to persuade more

people to go to college. If almost everybody has a college degree, getting one

doesn't differentiate you from the pack. To get the job you want, you might

have to go to a fancy (and expensive) college, or get a higher degree.

Education turns into an arms race, which primarily benefits the arms

manufacturers-in this case, colleges and universities.

The screening model isn't very

fashionable these days, partly because it seems perverse to suggest that

education doesn't boost productivity. But there's quite a bit of evidence that

seems to support Arrow's theory. In recent years, more jobs have come to demand

a college degree as an entry requirement, even though the demands of the jobs

haven't changed much. Some nursing positions are on the list, along with jobs

for executive secretaries, salespeople, and distribution managers. According to

one study, just twenty per cent of executive assistants and insurance-claims

clerks have college degrees but more than forty-five per cent of the job

openings in the field require one. "This suggests that employers may be

relying on a B.A. as a broad recruitment filter that may or may not correspond

to specific capabilities needed to do the job," the study concluded.

It is well established that

students who go to elite colleges tend to earn more than graduates of less

selective institutions. But is this because Harvard and Princeton do a better job

of teaching valuable skills than other places, or because employers believe

that they get more talented students to begin with? An exercise carried out by

Lauren Rivera, of the Kellogg School of Management, at Northwestern, strongly

suggests that it's the latter. Rivera interviewed more than a hundred

recruiters from investment banks, law firms, and management consulting firms,

and she found that they recruited almost exclusively from the very top-ranked

schools, and simply ignored most other applicants. The recruiters didn't pay

much attention to things like grades and majors. "It was not the content

of education that elite employers valued but rather its prestige," Rivera

concluded.

If higher education serves

primarily as a sorting mechanism, that might help explain another disturbing

development: the tendency of many college graduates to take jobs that don't

require college degrees. Practically everyone seems to know a well-educated

young person who is working in a bar or a mundane clerical job, because he or

she can't find anything better. Doubtless, the Great Recession and its

aftermath are partly to blame. But something deeper, and more lasting, also

seems to be happening.

In the Goldin-Katz view of things,

technological progress generates an ever-increasing need for highly educated,

highly skilled workers. But, beginning in about 2000, for reasons that are

still not fully understood, the pace of job creation in high-paying, highly

skilled fields slowed significantly. To demonstrate this, three Canadian

economists, Paul Beaudry, David A. Green, and Benjamin M. Sand, divided the

U.S. workforce into a hundred occupations, ranked by their average wages, and

looked at how employment has changed in each category. Since 2000, the

economists showed, the demand for highly educated workers declined, while job

growth in low-paying occupations increased strongly. "High-skilled workers